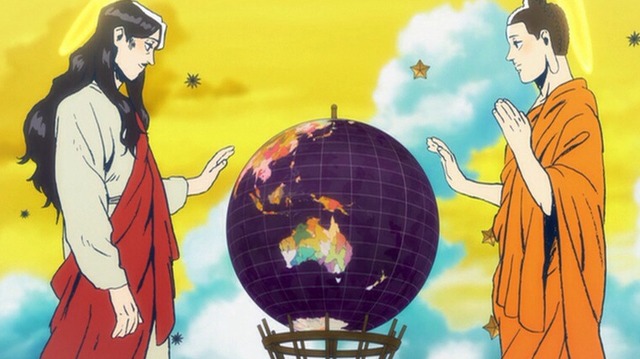

Saint Oniisan (Saint Young Men, 2013) is director Noriko Takao’s recent feature-length film adaptation of Hikaru Nakamura’s popular manga of the same name. Set in modern-day Japan, the film—true to its source material—is primarily a strife-free outing for its viewers, promoting tranquility and a sort of harmonic convergence for an increasingly relativist transnational society.

Divinely ordinary and extraordinarily funny, the film (drawing heavily from Nakamura herself) manages to incorporate the patriarchal figureheads of two of the world’s most prominent religions into a comedic work that is neither profane nor controversial (the latter could arguably be a point of criticism, as the film apparently has no specific agenda to assert, religious or secular; in fact, there is virtually no plot-related conflict within the film whatsoever). Heart-warming hilarity outweighs any potential sacrilege: even after ninety minutes of screen time chock-full of offhand religious references, spiritual slapstick, and unintentional ‘miracle mayhems’ (Buddha’s accidental ascetic radiance or Jesus’ parting of the public pool), the film emerges with its position of theological neutrality in check. Contrary to the view a typical (especially Western) analytical process might favor, I would contend that this air of neutrality does not result in spite of the film’s religious overtones, but rather because of them, as Zen Buddhism is about accepting the world as it is. As the late celebrated film critic Donald Richie once said, “in traditional Japanese narrative art one celebrates and relinquishes it” (52).

With regards to aesthetics, the film—however purposefully surface-level it may be—has more than a few tell-tale signs of cinematographic conventions associated with anime traditions, both long-standing and popularly recurring. As with almost every anime ever created, Saint Young Men makes effective use of the ‘pillow shot’ developed and pioneered by movie-making giant Yasujiro Ozu. (The fact that it is especially cost-effective in animation is a beneficial side effect.) Beyond the traditional usage, however, director Takao may have purposefully taken this technique one step further for this specific project: columnist Carlo Santos has said of Nakamura’s original work, “its brilliance comes not from purposefully trivializing two of the world’s great religions, but by highlighting the quirks of the secular world when these famous religious figures are placed in it” (animenewsnetwork.com).

Towards the end of the film, when the neighborhood vendors and tenants (and, of course, we spectators) think “Long Hair” and “Punch” (Jesus and Buddha respectively) have departed, we are treated to extended dialogue from the people whose lives were directly affected by the two self-proclaimed sages. The daily routine of housewives, storekeepers, schoolchildren, and even several yakuza are suddenly back to normal—though, as they experience, normalcy is never again attainable after a profound spiritual encounter (whether you are aware of having one or not). Though the scene does not consist of “true” Ozu-endorsed pillow shots, as part of a Japanese film it is obliged to pay minimal homage, and through pseudo-Ozu-style montage we are allowed to see the ripples of these religious founding fathers’ actions reverberate upon the secular civilization of the present.

Though the lack of internal conflict or external contention should, by many definitions, make for a weak film, Saint Young Men is saved in part due to its status as an adaptation (as opposed to being a truly original production) and extension of a preexisting work, i.e. an accompaniment to, and advertisement for, a larger brand (instead of being a standalone product). Its ultimate salvation, however, comes from its previously mentioned non-confrontational tone and its ideal position to act as both a keen observer of the current culture and a gauge of theological fusion to be measured by future generations.

Due to its faithfulness to its parent material’s identity, the nature of its slice-of-life roots, and its own distinct ‘sutra of the sublime,’ Saint Young Men is destined to be remembered fondly by the ‘hip’ Buddhist-Christian hybrid society which fostered it; and it has more than a fair chance of being well-remembered within Japanese cinematic history at large—if only due to the sheer novelty of seeing Jesus Christ and Gautama Buddha living like well-to-do college students vacationing in Japan.

© 2016

Works Cited

Richie, Donald. Ozu. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1974.

Print.

Santos, Carlo. “Little Twin Stars.” Right Turn Only!! Anime News Network. 27 Apr.

2010. Web. 4 Feb. 2016.

Originally posted here (original version).

Revised and re-posted with permission here (current version).