It is a reassuring fact that amidst the hustle and bustle of the twenty-first century, a quintessential Japanese film can still be made. In This Corner of the World (2016) is a satisfying mixture of light humor, domestic monotony, and depictions of life-altering trauma characteristic of archetypal Japanese cinema. An adaptation of a previously published manga—marketed as To All the Corners of the World (2007–2009)—the film was directed by Sunao Katabuchi, known internationally for directing another manga adaptation in the form of philosophical gore fest Black Lagoon (2006). Yet despite the Japanese animation market’s current penchant for overreliance on commercially viable source material as a guide to releasing animated titles, like the aforementioned television series Black Lagoon, the feature-length In This Corner is an organism unto itself, a truly cinematic piece specifically crafted for the screen by a skilled auteur.

As previously mentioned, the film exists as a blend, a potpourri of emotional extremes that, while fairly typical of Japanese cinema since its inception, historically has not always been appreciated by spectators of other nationalities. Recounted numerous times by film critic Donald Richie (a recognized authority of Western commentary on Japanese cinema), the brilliant Soviet film theorist Sergei Eisenstein is said to have disliked Heinosuke Gosho’s Tricky Girl (1927) precisely because it was both comedic and tragic. Though these seemingly antithetical combinations are not exclusive to Japanese filmmakers by any means, they remain comparatively rare in the West while continuously cropping up in Japan up to the present day: in fact, in homage to aforesaid filmmaking pioneer, ‘Gosho-ism’ is a term known within circles of film criticism as “a style incorporating something that makes you laugh and cry at the same time” (A Hundred Years, 50). Such moments abound throughout In This Corner of the World as the tranquility of daily rural life is repeatedly interrupted by air raids and the cannon fire of war.

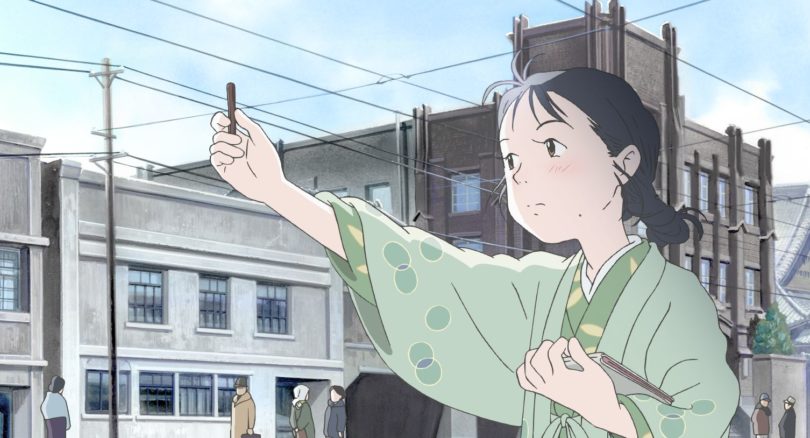

But it is more than stylistic evocation of conflicting emotions that, by most definitions, makes any particular film quintessentially Japanese. Perhaps to the layperson and critic alike, there is one multifaceted component of a Japanese film that is indicative of its heritage more so than all others: atmosphere, which is realized through, and exemplified by, leisurely pacing. Despite its World War II backdrop and the meticulous chronicling of time within its narrative, In This Corner meanders when it comes to plot. One may, somewhat legitimately, find the pace of narrative flow (complete with flashbacks and plenty of exposition) labored; or, like main character Suzu herself, aloof, lacking drive or a straightforward sense of purpose. When viewed through the proper lenses of criticism, however, it is clear that this is neither accidental nor a shortcoming of the film: as Richie once put it, “to think that getting the point is the point of Japanese films is to miss the point entirely” (Japanese Cinema, 16). If one is seeking a simple point to the film—or indeed, to almost any Japanese film—then disappointment will surely follow.

Created by a people with an ancient culture, Japanese cinema often reflects deep-rooted sentimentality (both in a general sense, as a way of seeing reality, and in terms of direct appeals to nostalgia through the use of cliché), and is continuously nurtured by a fondness for intellectual mastication and emotional reflection. The appropriate way to view In This Corner of the World, therefore, is how one would approach a masterpiece of Yasujiro Ozu, or how Suzu and her family approached each passing day: by quietly reveling in the present, and experiencing each cicada chirp or raindrop as it comes, in the moment. This may be difficult for modern-day audiences watching a period piece, since through the lens of hindsight we viewers obviously bring our own ‘luggage’ in the form of historical knowledge to the screening; an ominous feeling, much like Suzu’s anvil cloud portending a deluge (while foreshadowing another type of cloud), is stirred within us ever so slightly at each casual mention of Hiroshima prior to August of 1945. Yet even still, amidst scenes of struggle, strife, and outright carnage, within the film there are paradoxical instances of genuine relaxation and stillness, innocent frivolity and childlike humor.

That isn’t to say that the film censors any violent content, or shields its audience from anything unpleasant. Nor is it untrue to its themes or characters, insofar as it manages to allow characters like Suzu (and others, such as her husband Shusaku and sister-in-law Keiko) to change according to their experiences—be it caringly cultivated love or sudden, devastating loss—while remaining true to their core personalities through a balance of childhood dreams left in the past, adult obligations existing in the present, and hope in a future filled with enduring relationships. Case in point, the purpose behind scenes showcasing artistic mediums including painting and sketchbook doodling in lieu of otherwise graphic wartime action is not censorship. Colorful paints and symbolic imagery are ways in which Suzu as an artist interprets reality, while specific applications of various euphemistic techniques (e.g. exploding bombs becoming paint drops) seek to accomplish a directive not unlike the artistic movement of Expressionism. It is not an objective representation of empirical reality, but an expression of feelings, of ineffable psychological needs born out of indelible life events. (Painter Vincent Van Gogh often comes to mind during such narrative sojourns, as does avant-garde animator Norman McLaren when Suzu last sees her niece Harumi.) Furthermore, it is not the events themselves that bear the study of focus in the film—even though, like those suffering from survivor’s guilt, Suzu does intensely scrutinize her actions and hypothetical scenarios leading up to the time-delayed explosion that maimed her—but rather their aftermath: brokenness of one’s body, family structure, and morale, and, most crucially, how one finds resolution in the wake of tragedy.

In This Corner of the World contains subject matter that has been depicted in various media countless times, and it strongly adheres to orthodox Japanese cinematic tradition stylistically. But as early animators have always sought to do (and for which all filmmakers ought to strive ceaselessly), In This Corner offers novelty to any would-be spectator. And even within an economic environment that favors adaptive screenworks over new stories, the contemplative mood and celebration of familiarity endemic to Japanese art is a desperately needed reprieve from mechanized modernity. In many ways, Japan is a land where the past is still present. Whether through formal ritual or a general proclivity to savor established form, the Japanese people tend to reflect intently upon something, to reexamine the most innocuous detail or relive the humblest of life occurrences; it is no wonder, then, that the comparatively recent events of World War II, complete with the first usage of nuclear weapons and the ushering in of a new atomic age, have become a recurring feature of Japanese culture ever since. But as long as there are demonstrably beautiful works like In This Corner of the World within its annals, Japanese cinema, like its people, has a bright future.

© 2017

Works Cited

Japan Travel Bureau. Japanese Cinema. Rev. ed. Translated by Donald Richie,

Anchor Books, 1971. Print.

Richie, Donald. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a

Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Rev. ed. Kodansha, 2005. Google Books.

Web. 5 Sept. 2017.