Studio Ghibli’s Only Yesterday (1991) is a sublime example of twentieth-century Japanese filmmaking that, surprisingly, has only just started to be experienced by U.S. and Canadian audiences en masse due to its North American theatrical run occurring twenty-five years after its premiere. Directed by Isao Takahata, and with producer credits for fellow industry veterans Hayao Miyazaki and Toshio Suzuki, Only Yesterday is as much classic Ghibli as it is homage to Japanese filmmaking giants of yesteryear.

Adapted from a preexisting manga, the film takes considerable creative liberties with the main character Taeko and her role as a framing device, making it a truly distinct work worthy of admiration not only in manga and anime circles, but in broader academic fields of Japanese film history and film theory.

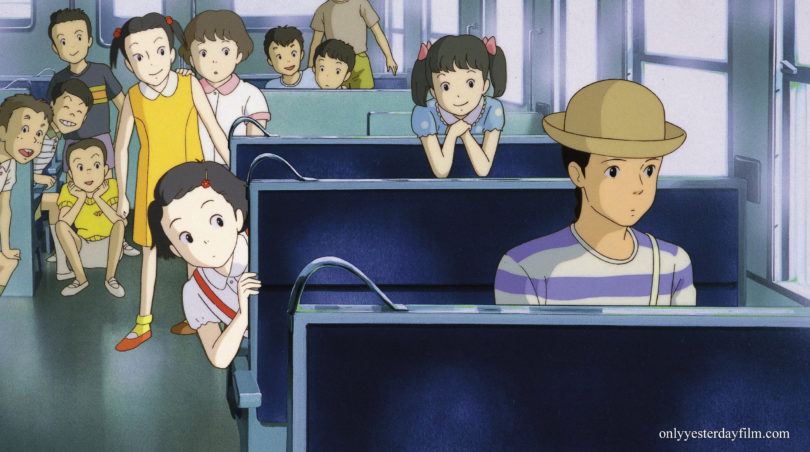

In addition to being an entertaining retrospection of Japanese society in the 1960s, the film itself touches viewers of any nationality or era delicately yet profoundly due to its ability to subtly convey the ephemeral qualities of human memory. After all, for better or worse, one’s own memories—or, rather, an individual’s perceptions of memory—define and reinforce concepts of identity in one way or another. Along with vivid animation, the fact that the catalyst of the narrative is Taeko’s personal recollection of her childhood gives the audience a feeling of familiarity and intimacy with the protagonist on par with any live-action production.

As unforgettable as certain moments in life may be for a person (such as when fifth-grade Taeko is struck by her father), the film’s aesthetics also allude to the fleeting nature of the past. In almost every scene involving an extended flashback on the part of Taeko (as an adult, recalling her days in grade school), the edges of the frame in any given shot are indefinite, inexact, eventually fading into a white background evocative of an unpainted canvass.

In cinematographic form, Only Yesterday is truly Japanese in its identity; as opposed to a classical Hollywood approach of the West (now emulated the world over), there is a refreshing lack of emphasis on linear narrative, plot, and definitive resolution of events. But this style of filmmaking, now integral to many notable niches of Far Eastern cinema, can trace much of its origins to one particular filmmaking pioneer of the early twentieth century: Yasujiro Ozu.

Unconventional even by Japanese filmmaking standards both then and now, Ozu has been known to say “plot bores me” on more than one occasion (qtd. in Richie, 19). Instead of making characterization, form, and mise-en-scène beholden to traditional notions of narrative, Ozu elevated spatial arrangements and temporal relations to an equal status of importance with the onscreen action. Similarly, a decidedly contemplative mood, along with unconventional trappings of time and accentuation of familial bonds, gives Only Yesterday a style unmistakably reminiscent of Ozu classics like Tokyo Story (1953).

Consequently, though it lacks a fantastic setting or an action-packed plot, Only Yesterday gently commands the attention of spectators precisely because, like life, much of it is mundane and inconclusive: its diligence to form gives one a renewed perspective of the ordinary, and as authors Bordwell and Thompson once remarked, “As a result, even a simple narrative like that of Tokyo Story becomes fresh and fascinating” (401). Perhaps, cleverly enough, this unexpected phenomenon of Ozu-inspired nostalgia (for film critics and older Japanese viewers, at any rate) was as intentional and meticulously planned as every other artistic and technical element of the film.

Whether due to its unassuming subject matter, its inclusion of commonly recurring Ghibli motifs (including symbolic, romanticized depictions of trains, traceable in no small part to Ozu), or simply the fact that its official North American home video release occurred during an age of global hyperconnectivity, Only Yesterday is destined for longevity within the annals of film history. As it is continuously celebrated and re-evaluated, its wistful charm will likely only increase its own nostalgic tinge of sentimentality.

© 2016

Works Cited

Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. Film Art: An Introduction. 8th ed.

New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, 2008. Print.

Richie, Donald. Ozu. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1974.

Print.

Originally posted here.

Re-posted (read aloud, by yours truly) with permission here.